Beyond the tourist-lined shore of Sausalito, past the seaside restaurants and boutiques, lies the Richardson Bay.

It’s the shallow estuary that surrounds southeastern Marin County, often featured in visitors’ photos for its sparkling waters and picturesque ships docked out in the water.

Underneath the surface, however, lies the fragile underwater meadows of eelgrass that make up the cornerstone to marine life in the Bay Area.

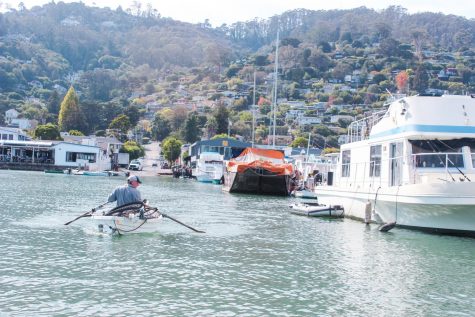

There’s another vulnerable population floating above the surface as well: though they are visible to the passing eye, many visitors don’t realize that the 86 vessels parked on top of the bay are actually homes to veterans, passionate maritimers and those seeking shelter amidst the Bay Area housing crisis.

Richardson Bay had its peak population of long-time residents in 2016, when over 235 residents called the waters their home. Some have lived out there for generations.

“There’s families out here that are like fifth generation. They were born out here,” said Clyde Terrell, one resident of the anchorage.

“That’s not homeless boat dwellers, that’s a culture,” said Arthur Bruce, another resident of six years.

A few of the 86 long-term vessels on the Richardson Bay. Some of the residents on these waters have lived here for generations. (Olivia Wynkoop)

“Anchor-outs,” they call themselves, and though their history links back to World War II, their presence hasn’t been met with much enthusiasm from environmentalists and oversight agencies for decades.

The conflict further escalated after the state’s Bay Area development oversight agency, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, threatened legal action if the Richardson’s Bay Regional Agency didn’t begin to enforce their 72-hour anchorage law and transition long-term residents out of the bay.

“We’ve been led to understand that the RBRA wasn’t working fast enough to deal with the different concerns that they have,” said Priscilla Njuguna, Enforcement Policy Manager at the BCDC.

Historically, the RBRA has allowed mariners to anchor in the bay long past their 3-day policy initiated in 1987.

“The big push is that we have to find homes for these homeless people, but it’s like no, this is their home. They’re not homeless, and even if they had a million dollars, they’d just have a nicer boat and they’d still live on the boat,” Terrell said.

Amid a settlement agreement between the two agencies in mid-August, only the 14 vessels in the agency’s safe and seaworthy program can temporarily anchor out of the bay until 2026. For the others, they have until December of 2024 to find housing elsewhere.

Some residents allege there are loopholes in the agreement that force them to move out sooner, rather than later.

The RBRA, backed by a coalition of housing and environmental advocates, is now tasked with balancing habitat protection, anchor-out’s concerns and public agencies’ capacity to house people during a worsening housing crisis.

Anchor-outs Clyde Terrell and Arthur Bruce try to find a place to park in Sausalito’s only public docking spot. The dock is filled with little rowboats, many of which are the anchor-outs’ main form of transportation to and from shore. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Meet the anchor-outs

Terrell steering the “Reel Nauti” back to shore on a sunny afternoon in October. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Terrell revs up the passion project he’s been working on for months at Sausalito’s only public docking spot on a still, sunny afternoon in October.

Her name is Reel Nauti, an orange-and-white service boat for the anchor-outs. With her help, Terrell hopes to transport anchor-outs to and from shore, drop off essential supplies and maybe even bring out social workers and outreach providers to isolated residents.

In the first few weeks the vessel has been in service, Terrell said he’s already towed five boats, delivered water and groceries and provided plenty of rides for people in need of an outing.

Beside him is a resident loading up cases of water, toilet paper and other goods to a small rowboat. Some use kayaks, and others have motorized fishing boats, but a setup like this is traditionally how most anchor-outs get to shore for goods and services.

For many, these outings are few and far between. Living in the middle of the bay with limited space means everything must be rationed and serve a purpose.

“One of the things that’s different about this lifestyle and culture is patience,” Terrell said. “Everything takes 10 times longer, things are 10 times harder. Even the little things that people take for granted, like fresh water,” Terrell said. “Having something like a service boat is a big deal, to have the ability to give those resources to people who otherwise wouldn’t have them.”

One anchor-out bringing groceries like water and toilet paper back to his vessel

at the Sausalito public dock. (Olivia Wynkoop)

But the anchor-outs say it’s worth it. Alongside Terrell sits Arthur Bruce, who moved out to the anchorage in 2015.

Bruce says the sense of community out here is something he’s never seen on land. And the fact that he doesn’t have to lock his door when he leaves is nice, too, he said.

“My mind’s really sharpened in the years I’ve been out here, just being forced to engineer things and make it happen with what I have and the tools I have on board. It’s a good exercise for your mind,” Bruce said. “I learned fast and hard, and I talked to the old-timers who’ve been out here doing it a long time. They showed me how to do it right, and that’s how I do it.”

Terrell and Bruce make their way into the bay. Storms are expected to pop up next week, but today is all blue skies.

The two stop by a resident who’s lived out here for 20 years, who’s lovingly referred to as “Einstein” for his unruly white hair.

“Sometimes my bedroom view is here… or here….” Einstein said, with his arms sprawling across the San Francisco Bay’s key landmarks. They’re all in front of him — Alcatraz, the Bay Bridge and the entire skyline of San Francisco.

“He’s been scared to leave for months now to go to the doctor. Hopefully he’s feeling a little bit of reprieve,” Bruce said.

Bruce overlooks the Sausalito shore as he, Terrell and Chase make it back to the Sausalito public dock. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Playing defense during “marine debris” removal process

Anchor-outs like Einstein say they’re afraid to leave their boats because they think they’ll be destroyed by the RBRA without due process. Some say they skip out on doctor’s appointments and grocery hauls for fear they will come back to find a big advisory tag on their vessels.

CAPTION: One of the 86 vessels on the Richardson Bay. Many vessels on the anchorage are defined as “marine debris” to the RBRA. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Their concerns ramped up in the community when now-former Harbormaster Curtis Havel was tasked by the RBRA to clear out unseaworthy vessels and marine debris in the water by October 2021. During his two years of service, he whittled away more than 100 vessels from the anchorage, according to RBRA records.

The oversight agency refutes any claims that these vessels were occupied.

Havel has since stepped down from his position in October for “another professional opportunity,” according to Jim Malcolm, who was once Havel’s right-hand man and now the temporary harbormaster.

“We’re talking about an anchorage, not a marina. If you want to have a boat, and you want to leave a boat somewhere unattended, that’s what a marina is for. An anchorage is where a mariner comes in, drops anchor and keeps a watch on their vessel while it’s at anchor,” Malcom said.

Upon an outreach effort in 2019, the RBRA found that Richardson Bay had 190 vessels on it despite only having 100 people living there at the time. These unoccupied vessels, mostly used as additional storage or space for residents, posed an environmental threat to the oversight agency. The agency’s transition plan took priority to remove these vessels first before requiring any resident to move.

Malcolm laid out the marine debris process, which he said concluded in October. The next step for the agency is to create moorings for the bay’s 15 safe & seaworthy vessels.

Anchor-outs call out against the agency, claiming it misused the term “marine debris” on numerous occasions.

One anchor-out fired a flare gun at RBRA officials back in March after the Harbormaster towed away his alleged residence, which later led to officers deploying tear gas, pepper spray and other less-than-lethal methods after he refused to surrender during a search warrant, according to a Marin County Sheriff’s Office report.

But this is only one extreme case among the routine passive-aggressive remarks, name-calling or “other pleasantries” anchor-outs make against RBRA officials, Malcolm said.

Neither the Marin County Sheriff’s Office nor the Sausalito Police Department was available for comment at the time of publication.

Bruce joked about the times he’s tried to ruin Havel’s media interviews, “rolling in hot with [his] little white bullhorn.” He said he tried to ruin every interview Havel’s done out on the water.

[infographic credit=”Twitter” align=”center”]

“Out here spreading lies to reporters, Curtis?” – Arthur Bruce 😂 https://t.co/EQjHjiGver

— Robbie Powelson (@RobbiePowelson) July 10, 2021

[/infographic]

For the residents, hostility is an attempt to make themselves heard, and most importantly, protect their home. To Bruce, he says the RBRA’s gray vessel feels like a bulldozer looming outside of his house.

An anchor-out rows to his vessel after buying groceries on shore. (Olivia Wynkoop)

“I have friends that [were] being threatened and terrorized by the [former] harbormaster, and a lot of them are elders in need of medical care and they’re afraid to go to shore, so often I get calls from my neighbors asking if I can guard their vessels while they’re at work or at appointments or just simply need to go get water,” Bruce said.

Housing advocate of the California Homeless Union Robbie Powelson cited at least 13 individuals who lost their homes because the RBRA mislabeled their vessels as marine debris. He alleges they use the law with the intention to remove everyone from the anchorage as soon as possible.

“They’re systematically destroying people’s community without any kind of consideration for the impacts of using violence to try and achieve their environmental goal,” Powelson said. “I think the use of violence is being way too normalized, taking people’s property and their homes without any kind of compensation, without any kind of due process is shocking.”

He mentioned Robyn Kelly, who filed a lawsuit against the oversight agency and Havel for $1 million for allegedly destroying her power boat under the agency’s marine debris policy, despite the fact that the vessel was her primary residence.

“They’ve been calling every boat they take marine debris, unoccupied marine debris, which actually is totally misapplied. They’ve taken seaworthy boats, boats that work, boats that are federally documented, because when they apply that particular statute, there’s no way to appeal the process,” Powelson said.

Eelgrass sustains a large part of the San Francisco Bay’s marine life. (Creative Commons / Claude Nozères)

How eelgrass plays a part

Richardson Bay is the second-largest eelgrass estuary in the Bay Area for marine life, sustaining life to 90% of the region’s Pacific herring population and supporting tens of thousands of water birds a year.

It also has become a hot commodity in the conservation sphere after recent talk of its ability to mitigate coastal erosion and effects from climate change.

Eelgrass has the power to reduce ocean acidity levels up to 30%, reversing the effects of climate change-initiated acidification, according to a recent six-year study by the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Over the years, a coalition of environmental groups and policy naysayers cite human presence as the leading cause for the destruction of eelgrass beds, which also links to the decline in bird population sizes in the area.

Barbara Salzman of the Marin Audubon Society said long-term anchor-outs create “crop circles” in the marine floor as their anchors shift around during storms and tide changes.

Boats circling around their anchors in Richardson Bay causes “crop circles” in eelgrass fields. (Patrick and Julie Belanger, The 111th Group, Inc.)

These circles, though seemingly only causing a minute impact on the eelgrass in the 19th century, became one of the greatest forces in eelgrass destruction as more vessels moved in, she said.

Between 2009 and 2014, over 900 acres of eelgrass beds in the San Francisco Bay were lost, and 25 to 41 percent of the eelgrass beds were damaged from long-term vessels alone, according to a study backed by Audubon California.

“This is the second largest [eelgrass] bed in the bay, and it’s just being eaten away by these vessels. Many of them are derelict, there’s nobody even living on a lot of them, or people just have their junk on them. It’s really a pretty awful scene, even for some of the people who are living out there,” said Salzman.

The Richardson Bay Audubon Center & Sanctuary cites the bay as the most suitable area for restoration efforts within the San Francisco Estuary.

Salzman admits, however, that bringing back eelgrass in scarred areas is not clear.

“For eelgrass, it’s not so clear how to restore it, so that’s another problem the longer this goes on,” Salzman said. “They need to be beginning to work on restoring some of these areas that have been so damaged, and you know the past methods are not entirely clear.”

Keith Merkel, an ecologist with Merkel & Associates, studies eelgrass populations along the West Coast, from Alaska to Mexico. He first started noticing the crop circles from moorings back in the 90s.

At first glance, the restoration efforts seemed simple enough. Move the moorings out of the eelgrass, restore the eelgrass, and keep the water use areas up to standards to protect the populations.

In his 90 different eelgrass restoration he’s been a part of, Merkel typically uses “bare root planting” methods, meaning a small amount of eelgrass from donor sites is planted across an area, and it later spreads itself throughout the marine floor.

What he’s learned over his work with environmental concerns, however, is that restoration efforts cannot be led in a vacuum. Especially in a Bay with such a deeply rooted history for anchored-out residents.

“I think what’s going on right now is efforts to accommodate and to prolong the process to allow time to help people find alternatives to being on the Anchorage. I think that the toughest part about this is not the science or the eelgrass or the restoration, it’s really the social dilemmas,” Merkel said.

These mooring scars pose new challenges to the traditional “bare root planting” method. A vessel anchored out for a long period of time continuously disturbs a settlement and creates craters in the ground, and the craters often fill with ship-related debris and algae that is unsuitable for a restoration environment, Merkel said.

One problem to work out is figuring out if donor eelgrass samples will naturally slit into the ground at an acceptable rate to produce enough eelgrass in the scarring, or if conservators will need to backfill the crop circles.

Researchers can start looking into best practices for the Richardson Bay now, Merkel said, as the damage on the marine floor far exceeds the amount of live-on vessels currently inhabited on the bay.

“Certainly in the recent years, there’s been an effort to curb the number of vessels coming in, so if you stop the vessels coming in and take out the vessels that are not occupied, effectively the boats that have been abandoned or the floating branches of two or three vessels owned by one person, there is still a lot of ground that has been opened up.” Merkel said.

Merkel is also hopeful about the RBRA’s proposed Eelgrass Protection Plan, which creates a new anchor zone specifically for transient vessels.

“The good news is that there is a path forward to attract it and it’s not in a real strict enforcement structure,” Merkel said. “It’s more a matter of how we work with a timeline to accomplish what is necessary. That’s really kind of the way it’s been framed and seems to be working out pretty well.”

Chase overlooks Richardson Bay as he talks about the challenges anchor-outs face in finding ample housing. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Boat jail or city-issued tents. What’s your pick?

Terrell and Bruce make their way to a vessel called the Jubilee to pick up Jeff Chase, the community rabbi. He greets them with a wave, captain hat on head.

“Super orange!” Chase said. It’s the first time he’s seen the Reel Nauti in action.

Terrell told him he crafted her with all recycled materials — every piece was taken from dumpsters, donations and sunken, abandoned boats at the bottom of the Sacramento River, down to the control boxes, which were hand-fabricated out of wood and fiberglass.

“Even the little flag and the little jack staff was from the bottom of the river from a wreck. The flag was black from sitting in the mud too long. I pressure washed it, scrubbed it and sanded off all the rot and repainted the Jack staff,” Terrell said.

The crew laughed together over Terrell’s meticulous attention to detail. Everything was handcrafted, everything was his.

“It’s so much better than the prettiest car,” Chase said.

Terrell, Chase and Bruce share snacks on Chase’s vessel, called the Jubilee. (Olivia Wynkoop)

They share Snickers bars and cigarettes as they chat about their qualms about marinas, or as Bruce refers to them, “boat jails.” Why pay $1,400 a month to be tied to a dock when you could be out in the water with that view as your backyard?

“Marinas have a kind of feel similar to a trailer park. When you’re anchored out, you have kind of the feel of, like, ‘I’m cruising in my RV and I’m stopping at the national parks’,” Terrell said.

Throughout the RBRA and BCDC’s transition verbiage, both agencies acknowledge the lack of housing options both for anchor-outs and those facing housing insecurity on Marin County land.

“There is a push on local, regional, and state levels to expand supply for persons who have very-low-to-medium income who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless, which includes many of those currently eligible for the Safe & Seaworthy program and legacy vessel status,” the RBRA’s Transition Plan reads.

“The RBRA will support efforts to connect people living on vessels with housing alternatives and services, as we are mindful of the challenges that face vulnerable members of this community,” said RBRA Board President and District 3 Marin County Supervisor Stephanie Moulton-Peters in a statement.

One tentative option for the agency is to encourage residents to move to liveaboard marinas, and some City of Sausalito funding can already make this possible for up to eight residents.

But people moved out here because they want to get away from all the noise, the three said. For some, it may be a preference to live out on the water as a maritimer; but for others, it’s a coping strategy to dealing with severe trauma from war, domestic violence or years of housing insecurity.

“Some just don’t deal well with intense social interaction for very long, so they prefer to live by themselves, and they feel safe and isolated from everything on their boat, where there’s not a lot of people,” Terrell said.

“Being on a boat is kind of healthy, with all the fresh air and some physical amount of labor. Now people are cooped up in a tent, and for some people, it’s very difficult,” Chase said.

And for most, moving out of the anchorage means swapping out their ship for a car or tent to live in. Chase referred to the tent encampment along Sausalito’s shore, which is largely made up of former martimers.

One resident’s setup in the Camp Cormorant Revival in Marinship Park. (Olivia Wynkoop)

Camp Cormorant Revival was set up in Marinship Park after residents were relocated from their original settlement in Sausalito’s Dunphy Park under a court order for safety concerns.

Children’s toys littered some residents’ squares of property, with one tent having a “please do not swear at the children” sign posted on its wall. Two residents chatted across a picnic table covered in books. And in the background were the sounds of the RBRA crushing marine debris.

“Everybody here is a star. But they don’t necessarily know it,” said one encampment resident at the table.

“Well, we’re not afforded the capability of making predictions or decisions,” replied Tom Quinn, who said he was at the camp for the last two weeks in mid-October.

He showed me one of the poems he scribbled on the inside cover of a book on the table:

A screaming night’s morning is screaming still.

Others of us wait until the exodus of the sane … untasteful leftovers malnourish a

homeless feast.

Rain won’t clean a thankless plastic spoon or its paper plate.

“They put this mariner’s camp literally at a rock-throwing distance from where they’re crushing people’s boats. Like, oh we made you all homeless, we’re gonna round you up in a fenced-in paddock, and make you watch it,” said Chase.

The camp’s mostly been obliterated by recent storms since October, and residents are looking for a way out.

Since the rainfall, five residents went to the emergency room for bacterial infections on their hands and feet, according to a press release from Powelson. A recent standing water sample collected under the Breje and Race laboratories revealed that the encampment’s ground had high levels of fecal matter and enterococcus.

Options are diminishing for where former maritimers and anchor-outs can live, safely.

“I am not going to sleep in a cesspool. Anyone willing to sleep in raw sewage can have my spot in Marinship,” said resident and officer of the California Homeless Union Tim Logan in a statement.

Mayor of Sausalito Jill Hoffman said the encampment began last January when a maritimer’s had no other housing options after his vessel was destroyed in a storm. Since then, the city’s spent over $500,000 in funds, mostly in litigation costs against the Sausalito Homeless Union, to address homelessness in the city.

Since storms hit Sausalito in October, the encampment has faced extreme flooding and fecal contamination on the ground. (Courtesy of Robbie Powelson)

“Sausalito will continue to work to identify housing alternatives, however, we cannot do this alone. We need Marin County to do more to provide housing support for those currently residing in the encampment and we need the County, and the RBRA, to do more to prepare housing alternatives for anyone who will be displaced from their vessels in the future,” Hoffman said in a statement.

Anchor-outs say the city should be using the funds to provide solutions, rather than keep it caught in red tape and salaries.

“They say they’re offering services and outreach programs, but all I’ve ever heard is talk. They spent something like 200 grand out of their homeless budget to hire this downtown streets team to cruise around with a big budget, handing out toothbrushes,” Bruce said. “I find it insulting.”