Saskia Hatvany

On top of a ridge in a secluded corner of Butte County, California, there is an eerie quiet. What was once a winding road lined with lush green conifers is now sparse and littered with blackened stumps. The bones of once-towering trees now lay strewn across the exposed ground.

The area burned in the 2020 North Complex Fire, which covered over 300,000 acres, and destroyed over 2,000 structures over the course of about four months. Less than two years after the fire was extinguished, thousands of standing trees have been replaced with bare ground, blackened stumps, and piles of brush as far as the eye can see. Every now and then, the roar of a logging truck breaks the silence, as it barrels down the road with yet another load of charred logs.

This is the work of post-fire logging, also referred to as “salvage logging,” a practice that has been controversial since the 1990s, when “The Salvage Rider” proposed to exempt salvage logging operations from public challenges under environmental laws — a proposal that was ultimately shut down after widespread public protest. Since then, a growing number of scientists have spoken out against the practice.

“Most people think that these big burn patches are the end of the forest, death in the forest, when in fact it really is a circle of life. You can’t have one without the other,” said Dominick DellaSala, who is currently the chief scientist at the nonprofit Wildlife Heritage.

In 2011, DellaSala thought he knew what a healthy forest was. He had been studying rainforests for about 30 years leading up to the publication of his book on boreal and temperate rainforests. One year, in early Spring, he took a hike with his then 8-year-old daughter near his home in Ashland Oregon, when they came across a patch of forest that had been severely burned several years earlier.

To their surprise, the landscape was teeming with butterflies, birds and insects. Fascinated, he began to study post-fire landscapes alongside Chad Hanson, another leader in the field of wildfire science. What they found changed their perception of wildfires entirely.

“We were getting levels of biodiversity that were comparable to old-growth forests,” DellaSala said.

Yet, following a recent rash of intense fire seasons in California, post-fire logging has been occurring across the state’s forests at an accelerated rate, as timber companies who own large swaths of the land rush to recover economic value from their now-charred investments.

Burned trees have an expiration date of around 18 months before they become unharvestable. In order to salvage the economic value, timberland owners apply for Timber Harvesting Plan exemptions through CalFire, which allow for timber companies to skirt the normal environmental review process so they may perform an “emergency” logging operation.

In 2021, over 63,000 acres were logged under emergency Timber Harvesting Plan (THP) exemptions due to fires, a 50% increase since 2018, according to CalFire’s annual Director’s reports.

This is of no small significance, as Sierra Pacific Industries, one of the biggest timber manufacturers in the world, owns over 2.4 million acres of timberland in California, much of it adjacent to National Forest land.

But private logs are not the only ones making their way to the sawmill.

After wildfires occur in National Forests, the United States Forest Service can auction off burnt trees on public lands to the timber industry. These charred logs are often sold below value, at a fraction of the price compared to unburnt logs, even if the wood can be worth just as much once it gets to the sawmill.

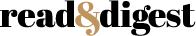

United States Forest Service documents show that in Shasta-Trinity National Forest there were at least four salvage timber sales amounting to about 350 acres in 2022. None sold for a price that exceeded $1.35 per thousand board feet (MBF) — the industry standard for timber volume measurement.

[pullquote speaker=”George Sexton” photo=”” align=”left” background=”on” background_color=”#ffffff” border=”all” border_color=”#888888″ border_size=”1px” shadow=”on”]Even at a $1.79 cost, that means that you’re getting a loaded log truck of old growth for less than the cost of a latte…” [/pullquote]

Document showing a timber sale on Shasta-Trinity National Forest that sold for $0.10 per thousand board feet.

“Even at a 1.79 cost, that means that you’re getting a loaded log truck of old growth for less than the cost of a latte,” said George Sexton, who has been a plaintiff on numerous post-fire logging cases in southern Oregon and Northern California.

One recent sale, referred to by Forest Service documents as “Antelope 30 Fire Salvage,” sold for $0.10 per ton to local logging outfit Franklin Logging, according to Forest Service documents. A typical logging truck can carry a maximum of 25 tons, which would price an entire truckload of wood at $2.50.

Meanwhile, wholesale timber prices reached an all-time high during the pandemic, soaring from approximately $400 to over $1500 per thousand board feet between 2018 and 2021, according to data from data firm Trading Economics. The price of a two-by-four at Home Depot doubled at the height of the pandemic.

“Bradley Restoration Project,” a 247-acre sale on the Shasta-Trinity National Forest sold over 3 million board feet of lumber for just over $4,500 in 2022, according to Forest Service records. The sale will also generate proceeds from road maintenance fees and other fees required. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

The Potential Environmental Impact of Post-Fire Logging

For the last five years, Ralph Bloemers has set up dozens of time-lapse and wildlife cameras in the forests of Oregon, Washington and California. Bloemers, a cofounder of the Crag Environmental Law Center, had been working on post-fire logging cases for two decades and wanted to observe post-fire landscapes with his own eyes.

What his footage revealed was a transformation that confirmed what scientists had been telling him for years.

“Within two years in these landscapes, it’s a jungle. There’s so much light, it’s a cacophony of noise, there are bees and birds,” said Bloemers, who is now the director of fire-safe communities at Green Oregon Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting Oregon’s forests.

Most of his cameras are placed in high-intensity burn patches where most, if not all trees are dead or dying. His footage captures images of bears, elk, cougar and other large mammals, even more frequently than in unburned landscapes.

A burned forest, otherwise referred to as a snag forest, two years after the 2020 Creek Fire which burned over 300,000 acres, mostly in Stanislaus National Forest. A growing body of research has shown that downed logs and charred snags are a valuable habitat for birds, insects and the mammals that feed on them. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

Dozens of scientific studies have shown that even intensely burned landscapes are an essential habitat for certain species of animals such as the Black-backed woodpecker which relies on downed burnt logs for its nesting cavity and burned forests for its highly concentrated food source, according to research published by the Forest Service itself.

“We shouldn’t even be calling in salvage…because salvage in the dictionary implies you take something from value from something that was destroyed. And while that might be the case economically, ecologically it wasn’t destroyed by the fire, it was rejuvenated,” DellaSala said.

DellaSala is one of over 200 scientists and environmental groups who signed a letter to President Joe Biden in 2021, urging him to roll back provisions within the bipartisan Infrastructure Bill that would subsidize post-fire logging on federal lands to the tune of $400 million. The letter warned that “post-fire clearcutting” would only contribute to further carbon emissions and could risk increasing fire severity.

This is because unlike green timber sales, in which the logger selectively removes certain trees and leaves the rest, salvage logging operations often result in most, if not all of the trees being completely removed — a practice that was banned on federal forestlands in Washington Oregon and California in the early 90s under the Northwest Forest Plan. Clearcutting is a term now almost never used by the Forest Service because of its negative association with deforestation and ecological harm.

Does the Forest Service Have a Financial Incentive to Log Burned Forests?

Critics of Forest Service salvage projects and plaintiffs in salvage logging cases have argued that employees have a conflict of interest in salvage sales, as the funds are able to remain in the agencies’ local budgets instead of returning to the United States Treasury.

Most of the revenue from salvage sales goes directly into the agency’s Salvage Sale Fund, rather than into the National Treasury. Each individual National Forest Agency is able to draw from its own Salvage Sale Fund in order to pay for future and current sales.

“It’s nice to make more money off a sale than less money. But ultimately, the reason I do my job is not for the Forest Service to make money, it’s to do the work and do the restoration,” said Katharine Bachmann, a timber sales administrator for the Shasta-Trinity National Forest

“I don’t gain anything personally, other than I feel good about having a job where I am directly affecting the local economy and the loggers that work on the projects.”

[pullquote speaker=”Katharine Bachmann” photo=”” align=”center” background=”on” background_color=”” border=”all” border_color=”#888888″ border_size=”1px” shadow=”on”]We’re selling them at rock bottom prices, mostly because we want to make sure we get the work done.[/pullquote]

Bachmann said that getting private companies to pay to do the work is advantageous to the Forest Service, because if the sales don’t go through, the Forest Service may have to pay for the work to be done anyway. Trees along roadways are viewed by the agency as a hazard to the public, so if they aren’t able to get loggers to harvest those trees, the agency would have to pay for the harvest itself with taxpayer dollars.

“We’re selling them at rock bottom prices, mostly because we want to make sure we get the work done,” Bachmann said. “If you want high severity burn habitat, there are thousands of acres out there.”

In the 2018 Carr fire burn area, which spanned over 200,000 acres, their department salvaged less than 400 acres and the bulk of the recent projects have centered around removing trees adjacent to roadsides so that they’re safe to drive on.

A patch of burned forest in the Stanislaus National Forest in Butte County. Photo by Saskia Hatvany

[pullquote speaker=”Kimberly Baker” photo=”” align=”left” background=”on” background_color=”#ffffff” border=”all” border_color=”#888888″ border_size=”1px” shadow=”on”]We’re paying to have our forests logged [/pullquote]

The Forest Service also receives more income from a sale than just the initial bid price. On top of their bid, the loggers must also pay additional fees to the Forest Service for road maintenance fees, slash removal and other costs.

However, even when logs are sold to a private company since the sale prices are so low, taxpayer money often subsidizes the practice anyway. In 2021, over $40 million was appropriated from congress to administer salvage sales, according to Forest Service budget reports.

“These are taxpayer dollars and it’s ridiculous how little industry is paying for these sales that are public resources that are owned by all Americans and have a lot of ecological value,” said Susan Jane Brown, a staff attorney with The Western Environmental Law Center.

Brown has been working on post-fire logging cases since she before graduated from law school in 2000. She said that the revenues from the sales are so low that they often don’t begin to cover the costs of administering the sale and post-harvest restoration work.

Smaller logs and leftover debris remain at the site of Bradley Restoration Project on Shasta-Trinity National Forest. Within the next year, the logging company will return to dispose of the debris. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

In one 2015 case, Karuk Tribe v. William Stelle, the cost of subsequent restoration was to be over 35 million, according to Forest Service’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, whereas the receipts from the sale were estimated to be $800,000.

“We’re paying to have our forests logged,” said Kimberly Baker, who has been monitoring national forests in California for 25 years.

In the case of the Bradley Salvage project, Bachmann said that the bid amount was doubled for road use, and other associated charges such as slash disposal, and she anticipates that it will triple once the loggers return to chip the remaining materials and haul them away.

The Bradley Fire salvage site in Shasta-Trinity National forests, several months after it was logged by Franklin Logging, which paid just over $4,000 for an estimated () tons of lumber. Forest Service employees expect to make triple that amount as the loggers are required to pay for other associated costs related to the sale.

This would put the sale revenue at around $15,000, or $4.60 per thousand board feet — still, a small price to pay for the logging company, which can that amount of wood to the sawmill for over 200 dollars, depending on tree size, quality and hauling distance, according to Bruce Daucsavage, President of Ochoco Lumber Co., a sawmill in Eastern Oregon.

“It’s pure supply and demand,” Daucsavage said. “When we know that the Forest Service wants to get out as burnt timber as fast as they can, will probably [offer] a bit a little bit less.”

According to Daucsavage, charred logs can lose 30 to 80% of their value, but given the right conditions they can be worth just as much as green logs.

In the Pacific Northwest, dead trees develop what is called a “Blue Stain,” grey-blue streaks on the inside of caused by a fungus transported by wood-boring beetles, which are attracted to burned trees. The result is a highly sought-after aesthetic that can fetch a premium at Home Depot.

Charred logs sit on land owned by Sierra Pacific that was salvage logged following the Bear Fire in Butte County. Blue stain begins to develop in logs once they are killed by fire or other conditions, and gives the wood a grey streaky appearance. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

Burned Timber is a Valuable Commodity

Gary Hendrix’s uncles started their sawmill business in 1897, in the small mining town of Oak Run in the Sierra foothills. In true pioneer fashion, the Philips brothers logged the surrounding forest using horses and carts to haul the heavy logs to the mill.

“When you live on your land, you get to know things completely different than an absentee landlord does,” said Hendrix, who prides himself on running a particularly environmentally conscious operation.

On the 920-acre property, many individual trees have been given affectionate names, and the property is bound by a legal agreement that permanently limits the use of the land for conservation purposes.

When Hendrix took over the management of Philips Sawmill in 1996, he said the value of a Ponderosa pine tree was around $600 per thousand board feet. Now, the same amount fetches closer to $300, he said.

“Right now, I would have to pay a logger to take it off of my property,” said Hendrix.

Philips Brothers Mill produces exclusively blue-stained wood from drought-killed trees harvested on their property because the market for it is simply more lucrative for them.

“They’re bright, beautiful on the inside — if you get them soon enough,” he said. “If you let them stand out in the forest for a year and a half, they’re rotten and they’re not worth a dime.”

But in recent years, fires have affected his business profoundly. As trees from salvage logging operations flood California mills, the value of his product has declined. Part of the reason, he believes, is Sierra Pacific Industries, which is the largest mill operator in the Northern California area.

“I talked to Sierra Pacific and they said that practically every truckload of burned logs they’re bringing in is out of one of their burned areas,” he said.

Sierra Pacific Industry is so large that they virtually control the California timber market, as they own the most land and the most sawmills of any other company in the state. Currently, the Home Depot website is filled with blue-stained pine boards produced by Sierra Pacific Industries, many of them listed for double the price of regular pine.

A time-lapse of a ridge in Butte County from 2019 to 2022, showing the rapid progression of post-fire logging after the Bear Fire. In this area, Sierra Pacific Industries requested to perform emergency logging operations on at least 1,967 acres, according to CalFire documents.

Even for the loggers, the business of post-fire logging can be lucrative, according to Zach Williams, the operations manager for the logging company Iron Triangle in Eastern Oregon. Williams said that salvage logging operations allow them to harvest larger trees, which are usually worth more. Under Oregon’s 21-inch rule, which was scrapped in 2022, only trees under 21 inches were able to be harvested in public forests, but those rules didn’t apply to post-fire logging.

“You can increase the value of the logs by about 50%,” Williams said.

Williams said that while the time constraints and conditions of the ground after a fire can be a challenge, salvage operations generally allow loggers to take many more trees in a given acre. The more they can harvest without having to pay additional fuel and hauling costs, the more profitable the operation.

“We never get that kind of volume per acre in a green harvest,” he said.

Aerial view of a patcg of forest in Butte County that was logged after the Bear Fire. Slash, debris and logs materials are often left behind by logging operations for months if not years. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

The Future of Salvage Logging on Public Lands.

Since the recent rash of wildfires in California, large-scale salvage projects have been proposed across multiple National Forests. One such project is the River Compex Risk-Reduction Project, which proposes to perform a salvage operation on over 5,000 acres of the Klamath National Forest.

Approximately 4,000 of those acres are on designated wildlife reserves and on late-successional reserves — areas of forests designed to preserve large old-growth trees under the Northwest Forest Plan.

George Sexton, who is the Conservation Director for the nonprofit Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center, is one of several environmentalists who are critical of the project and others like it.

“What’s the purpose of having a late-successional reserve if as soon as it burns, magically it becomes a timber matrix? We’re at a point right now where most of the acres are going to be affected by fires…that means that there is no such thing as a reserve,” Sexton said. “The last place you need to be doing salvage logging is late successional reserves way in the backcountry.”

Several months after the Bradley Fire Salvage operation was conducted on the Shasta Trinity National Forest, piles of slash and debris remain at the 300-acre site. The logs on this project were sold at a price of $1.35 per thousand board feet, or just a few dollars for a semi-truckload of logs. Eventually, the remaining slash materials will be chipped and hauled out by the logger to make way for restoration projects such as green trees. Photo by Saskia Hatvany.

Danika Williams, a Deputy District Ranger in the Klamath National Forest, said that the river complex project emerged primarily from a need to reduce fuels and to improve road conditions for both firefighters and the community. She said that any pushback on the projects, such as the ones raised by Sexton and others, is carefully considered.

“There’s no question that logging can have an impact on the landscape and especially post-fire logging,” she said. “We put a lot of pre-work into designing a project that minimizes those impacts…Unfortunately, we don’t always come to a good compromise,” she said.

One argument among forest service employees who work on salvage projects is that the new kind of fires in California are not natural, and therefore justify more dramatic action. Specifically, Williams said that following the Six Rivers fires in 2021, larger areas than normal contained not a single green tree, and this prompted concerns that there may not be seeds from green trees available to regenerate the forest. The result, they feared, would be a landscape more vulnerable to future high-intensity fire.

A 1951 Smokey Bear advertisement bemoans the “shameful waste” caused by forest fires, which have now been found to contribute immense ecological value to fire-adapted landscapes such as California. Courtesy of Smokeybear.com.

“We looked at where there were the largest patches of high severity fire on the landscape because we feel like that’s where there’s the most immediate need for management actions.” Williams said. “There are other locations where we’re not proposing any treatment…because we feel that that mimics more of that natural landscape condition that you would expect to see under more of a natural fire regime.”

Bloemers, Sexton and other advocates ultimately believe that salvage logging comes down to an ideology as much as the science. In the American West, multiple generations were taught fire ecology by Smokey the Bear, whose advertising campaigns often referred to fire as a great “waste” and painted it as an ecological disaster to be controlled and suppressed.

Smokey’s advertising campaigns are marked by a legacy of extreme fire suppression, which many now believe has contributed to forests long overdue for fires that scorched the landscape regularly thousands of years ago.

“Many people forget the closing scene to Bambi…it’s Bambi and all his forest friends in a charcoal forest,” Bloemers said. But people remember Bambi fleeing from the flames and that scariness. And that film alone has probably impacted people’s thinking about fire and wildlife more than every scientific paper put together.”