If the Walls Could Talk

Uncover the layers of the mysterious Westerfeld House in San Francisco, paired with a Black Lager

The Westerfeld House sits on the corner of Fulton Street and Scott Street next to Alamo Square on a sunny day. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

The History

If the house from the hit 1960s TV series The Addams Family was real, it would sit on the corner of Fulton Street and Scott Street in San Francisco. The giant five-story Victorian, known as the Westerfeld House, was built in 1889, stood out to its current owner, Jim Siegal, for its eerie resemblance to the spooky TV series.

“I love the house,” Siegal said. “It was my favorite house in the city. I’ve had my eye on it since I was a kid, and it was what inspired me to start buying real estate.”

Jim Siegal poses for a portrait in the tower of his home. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

Siegal, a self-taught restoration expert and contractor who owns six Victorian properties, bought the home in 1986 for $750,000. Siegal always had an affinity towards old Victorian homes, so when this iconic home came onto the market, he immediately knew what his next project would be.

“My goal was to restore the house and make it look like it would have in the 1880s, when it was first done.” Siegal explained.

Alamo Square, along which the house is located, is encircled by many famous Victorian houses in San Francisco, such as the Painted Ladies. These Queen Anne and Colonial Revival-style homes, painted in bright, light colors, make the dark purples, greens and golds of the Westerfeld House stick out like a haunted house on the top of a hill. All that’s needed to complete the fantasy are some headstones, ominous fog and witches riding around on broomsticks.

The complex architecture of this home is a hodgepodge of different Victorian styles. Siegal believes the mix of these Victorian styles, especially the Second Empire style, give the home its scary vibe.

“They [people] think of that as the quintessential ghost house,” Siegal said. “Whenever you see somebody drawing a spooky house, it’s usually a Second Empire or Queen Anne with a tower and a peak roof.”

Even though the 44-foot tower that provides 360 degree views of San Francisco was built in the Eastlake style, the mansard roof on top — accompanied with the other Italianate aspects of the home — are considered to be more Second Empire style.

The complex oddities of the house do not stop with its resemblance to old haunted homes or its assortment of architectural styles.

The Westerfeld House is the epitome of counterculture, attracting artistic and odd energies like a vortex as well as past tenants who left an electric, almost ethereal, mark on the home.

Original photos of the Westerfeld’s sit at the Westerfeld House along with other original artifacts. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

William Westerfeld, a German-born confectioner, had the house built for his wife and four children for $9,985 — an amount they never could have imagined would one day skyrocket to $1 million. They lived at the 1198 Fulton St. address for six years before Westerfeld died in 1895 and the house was sold to prominent builder John Mahoney.

Mahoney built many iconic buildings such as the Sheraton Palace Hotel and the Greek Amphitheater in Berkeley. He even rebuilt the St. Francis Hotel in downtown San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The 25-room house, equipped with 2 ballrooms, now turned apartments, served as the perfect location for Mahoney to entertain the wealthy socialites of San Francisco in the early 1900s. Mahoney’s inner circle consisted of radio pioneer and inventor Guglielmo Marconi and Harry Houdini, who both used the unseen power of the ominous tower of the home to conduct groundbreaking experiments.

Marconi used the tower to transmit the first radio signals on the West Coast, and Houdini reportedly tried to send telepathic messages across the bay to Oakland. Even in its early days, something about this tower drew people in like a magnet.

In 1937, three floors directly below the tower, a Russian colonel was murdered. Many believe this unsolved murder was over a woman. From 1928 to 1948, the Westerfeld House was used as a Russian Embassy for Czar Russians who fled the Russian Revolution. Even though they occupied this property during the height of prohibition, they used the ballroom as a nightclub and speakeasy.

“ Because it [the home] was considered to be a consulate of the Imperial Czars Russians, America didn’t recognize it in the 1920s,” Siegal explained. “The communists recognized the Czars, so they were allowed to have alcohol in here during the 1920s.”

The Westerfeld House attracted another group of outsiders during the `50s and `60s: Black jazz artists. The rooms in the home were turned into apartments and rented out by famous jazz musicians such as Art Lewis, Jimmy Lovelace and John Handy.

“When the bars were all closed on Fillmore, they brought everybody home and had jam sessions,” Siegal said.

According to Siegal, Fillmore street was the Harlem of the West. There were many Black jazz clubs and Black-owned businesses that brought famous Jazz players from all over the world to San Francisco. A short walk away from Fillmore street, the Alamo Square neighborhood was majority Black and seen as a ghetto.

This rough, segregated neighborhood drove away Charles Fracchia and his wife who bought the property in 1965 — the same year race riots broke out in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California.

“This was the black ghetto,” Siegal explained. “She was a Pacific Heights socialite, and said absolutely no way…We’re not moving in that ghetto.”

Fracchia put flyers up at San Francisco State, searching for tenants to fill the mansion. The Calliope Company, a Burning Man type group, rented the home in 1965 and it became the first hippie commune in San Francisco. The group was instrumental to the birth of the LSD hype in the Haight Ashbury scene.

For many young people in the 1960s, San Francisco was seen as a psychedelic heaven — a place where hippies could go and live out their trippy LSD fantasies. Siegal was one of these young hippies who moved out to San Francisco in search of the laid-back lifestyle in the big city.

The hippie room inside the Westerfeld House. This room contains Siegal’s memorabilia from his Haight/Ashbury hippie days. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

Siegal became friends with many members of psychedelic rock promoters The Family Dog, who took over the house in 1968. The Family Dog filled the Westerfeld House with psychotropic music, and would promote concerts at the Avalon Ballroom.

“I know a lot of this history because I know the Family Dog people, and one of them is a very close friend of mine, Fayette,” Siegal said. She was brought here by James Gurley’s wife, Nancy Gurley.”

The Family Dog also brought in many famous rock stars, such as The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company.

The rockstars and temptations of the music industry brought a darker time to the home.

“By 1968, everybody started getting off of LSD, and the Haight Ashbury was flooded with speed and heroin,” Siegal said. “Unfortunately, this house became a heroin den.”

It seemed as though the tower’s mysterious magnetic powers yet again claimed more victims. Siegal admits that by the last year they lived there, most of the members of the Family Dog would come up to the tower to use heroin and escape from the world around them.

If the walls of the Westerfeld House could talk they would tell the stories of enraged Russian Czarists, LSD crazed hippies and the hallways would be filled with funky jazz music and psychedelic rock. However, the pentagrams etched into the stairs ascending to the tower–now covered by carpet, tell a much darker story.

Kenneth Anger, a famed occultist filmmaker, rented the home in 1967. He filmed scenes for his abstract satanic movie “Invocation of my Demon Brother” in the home, using the tower as one of his focal points for ritual scenes.

Bobby Beausoleil was brought into the house by Anger to compose a soundtrack for Anger’s new movie, “Lucifer Rising.” But a fight between them prompted Beausoleil to leave.

“He [Anger] was in love with Bobby Beausoleil,” Siegal explained.

Siegal, who met the 95-year-old filmmaker, remembers one night when they sat in the tower reminiscing about Anger’s time at the house and his fight with Beausoleil.

“Bobby was messing with me,” Siegal recalls Anger telling him that night. “He stole my movie, and we broke up.”

Beausoleil would later become a member of the Manson family, and be the first member arrested for the La Bianca and Tate murders in 1969.

LaVey’s lion cub’s scratch marks on the doorframe leading up to the tower in the Westerfeld House. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

The odd vortex of energy in the tower of the Westerfeld House also had another frequent visitor during this time — Anton Lavey, the founder of the Church of Satan.

The residual energy from Satanic rituals Lavey performed in the tower lead many people to believe that the house is haunted by dark spirits. This residual energy can also be seen physically through Lavey’s pet lion’s claw marks forever scratched into the doorframe leading up to the tower.

TV shows like as Ghost Adventures and Conjuring Kesha have featured the home and claim to have had many unusual, terrifying and paranormal experiences, mainly in the tower.

“They think that the energy from the tower is making the cold air, which represents the spirits — at least, that’s what Zach told me from that Ghost Adventure show.” Siegal explained.

Even though the casts of the TV shows had many profound experiences during their overnight stay, Siegal — who has lived in the home for 36 years — has only had one truly terrifying experience with the paranormal.

Siegal’s bed in the Westerfeld House where he had a terrifying paranormal encounter. This was his only paranormal experience in the home. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

One night when Siegal was in bed, he felt the bed violently shake and someone plop into the bed with him — but no one was there. He assumed the shaking was an earthquake, but the chandeliers in his room were still.

“I turned around and said, ‘Look, I’ve been in this house for 20 years at this point,’” Siegal said. “‘I haven’t messed with you, don’t mess with me.’”

Siegal invited monks from the Hartford Street Zen Center to do a cleaning and blessing of his home.

“We had gongs and incense and everything going,” Siegal said. “We went room by room, and the monks clamped the cymbals and were shaking things. We had all the windows opened here in the tower and we invited all the spirits to be one with the universe in peace. I haven’t had any trouble since.”

The Pairing

These pairings were made by John “Magic” Montes De Oca, Co-head brewer and Operations Manager at Barebottle Brewing Co.

Black Lager

Barebottle recommendation: Dark Cosmos

ABV: 5.3%

Black Lagers and The Westerfeld House have roots in Germany. Black Lagers are German Lagers — although they were first brewed in Bavaria in the 1500s, long before there even was a Germany. Even though there are different versions of Black Lagers, such as Czech Black Lagers, the German Lager became popular in America in the nineteenth century.

“Germans came over and they brought their dark lager tradition with them,” Jeff Alworth, the author of The Beer Bible said. “When you look back at the first little breweries that they set up, they would have been making these dark lagers.”

Before lagers made their way to the United States, back in Europe, all lagers were considered dark in color. One of the earliest kinds of a dark lager was a Dunkel Lager.

“It was sort of the default before more modern techniques came in,” Alworth explained.

A GIF of Dark Cosmos, a Black Lager, chosen by Montes de Oca to compliment the history of the Westerfeld House. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

These German lagers used Munich malts that gave it a caramelized flavor. They would get their signature bread crumb and caramel flavors from the Maillard reaction that occurred when barley malts were heated up and would brown. These bread flavors mixed with the light bitterness from the hops gave the beer a mildly sweet, malt forward flavor. Many brewers will now use lighter malts, such as Pilsner malts, to make the beer have a lighter mouth-feel.

Over time, brewers in America discovered that if they added rice or corn to the grists, the malts that are ground in a malt mill at the beginning of the brewing process, the beer would have a pale color and light, crispy taste.

“We all think Germans are very mechanical, very perfect and clean to a tee,” John Montes de Oca, co-head brewer and Operations Manager at Barebottle Brewing Co. said. “That’s what a German lager typically is. There’s no room for error. They’re clean, they’re delicious and bright. But then you take a black lager, which even the Germans make, but it is the complete opposite. It’s no longer clean, you have roasty flavors and you might have different levels of sweetness. There’s so much variation within that.”

The Westerfeld House was built by Henry Geilfuss, a German architect, and meant to be a family home for the Westerfelds, a German family. What was once meant to be a home filled with laughter and family memories, over time turned out to be a home for the outcasts of society and the occult.

“It’s taking a German beer and almost bastardizing it a little bit,” Montes de Oca said about Black Lagers. “I feel like that’s what happened with this house. You take this beautiful, awesome San Francisco Victorian style house, and then all the people living in it just kind of took it down a weird path.”

To the German brewers of the 15th and 16th century, the modern day Black Lagers may seem as though it has taken a strange path.

The malts are still roasted, like coffee beans, before they are added into the beer to give them their caramel and bread flavors. However, modern techniques have made these Black Lagers more balanced and drinkable.

“We add the dark malt later in the mash process, as opposed to mixing in with everything else,” Montes de Oca said. “You also need to keep your pH higher because the lower pH will dry out more of the tannins.”

Montes de Oca explained that the amount of malt roasting selections available to brewers now is something early German brewers could never have fathomed.

“You have different levels of roast,” Montes de Oca explained. Even within the dark malt world, there’s chocolate malts, roasted malts, and black patent malts. There’s Carafa malts, which are the dark chocolate malt that has the husk removed.”

These rich and complex malt variations found in Black Lagers run parallel to the architectural and spiritual complexity of the Westerfeld House.

Unearth the history of the Old Ship Saloon in San Francisco, paired with a Hazy IPA

The outside of the Old Ship Saloon on the Corner of Pacific Avenue and Battery Street. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

The History

The Barbary Coast area of San Francisco, centered on Pacific Avenue between Montgomery Street and Stockton Street, was once a playground for many seedy characters during the Gold Rush.

Notorious sailors with a preference for a pint stumbled through the dirt streets from one saloon to another. Ladies of the night waited outside for men with money to spend. The famous San Francisco skyline was made up of decrepit wooden shanties and flimsy tents. The promise of gold brought thrill-seekers from all over the world to San Francisco in search of a place to get rich quick and live out their vices, regardless of the dangerous and poor conditions, according to Lana Costantini, Director of Education and Publishing at the San Francisco Historical Society.

“It was a dangerous place,” Costantini explained. “Women robbed men. People were drugged for money, shanghaied and kidnapped and put on ships. Go partying one night, and the next day end up on a ship that is on its way to China.”

Shanghaiing was a popular form of human trafficking in the 1800s and early 1900s and resulted in shanghiers like James Laflin being filthy rich, and their victims stranded on a ship thousands of miles away.

The Old Ship Saloon was home to much of this debauchery. Built during the height of the California gold rush, the saloon was constructed from the hull of the Arkansas, a ship that ran aground on Alcatraz in December of 1849. It was then brought ashore to start its new life on Pacific Street.

The Arkansas set sights on San Francisco in 1849, leaving from New York City,

never to return. For the 112 passengers, this six-month trip was no easy feat. Robert N. Ferrell, one of the passengers on the Arkansas, recalls the trials and tribulations of the voyage in his diary. According to Ferrell, the ship encountered treacherous storms, food shortages and disease.

Many gold miners who came to the Bay Area were so eager to get into the gold fields that they either left their ships or deliberately sunk them for insurance money. Since wood and other building materials were scarce and expensive, people decided to breathe life into these once-abandoned or damaged ships.

“The San Francisco Bay was littered with ships, just like the Arkansas, and most of them were just abandoned,” Eric Passetti, the owner of the Old Ship Saloon said.

These readily built structures were hauled into the city and landlocked into their final resting places as saloons, stores,

hotels and other industrial buildings.

The Arkansas was brought to the corner of Pacific Avenue and Battery Street in 1851, where a wooden plank was mounted on its side to serve as an entryway. A sign that read “Gude, Bad, an Indif’rent Spirits Sold Here! At 25¢ each” hung above the wooden door and the old ship was open for business.

Many of these buildings constructed from decaying, old wooden ships had no chance of surviving the fires that ravaged San Francisco in 1849 and 1851– not to mention how they would have toppled like dominos during an earthquake.

When people say that San Francisco has been built up, they mean it literally. Infrastructure from the old buildings, partially destroyed during fires and earthquakes, was used to raise and support the new buildings put in their place. According to Costantini, they did this not only because the infrastructure was already there, but also because it raised the buildings and the city up above the waterline, making it safer against possible flooding.

“I’d like to think that some of the brick in this building probably is from that original structure, because if you look at them, they’re like, black as if they were burnt,” Passetti explained.

Like other surrounding businesses, The Old Ship saloon was rebuilt in brick on top of the existing structure after the devastating earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed the existing wood building. What remained of the old hull– previously dismantled in 1857, sunk 25 feet into the mud of the waterline under the building, lying, basically untouched until almost 40 years later.

In 2016, crews found pieces of the old ship when doing foundation work on a neighboring seven-story condo building. They discovered dismantled pieces of the hull, cargo, including what appeared to be bottles and leather shoes — and most notably, a 15-foot wood fragment which looked to be the keel of the ship.

“They delicately covered it, per the request of the archaeological entity that oversaw the work, in almost like a concrete crypt,” Passetti said. “It’s totally preserved down there.”

Since its conception, the Old Ship Saloon has provided stiff drinks and cold brews for their patrons. The location is the oldest continuous saloon and bar address in San Francisco — 298 Pacific Ave. During its early days, the lawless San Francisco culture made for an “anything goes” attitude for the customers and employees of the bar.

The bar inside the Old Ship Saloon. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

James Laflin was as a cabin boy on the Arkansas and one of the first bartenders at the Old Ship Ale House, but his most notable job was a 50-year stint as a shanghier.

“He was the person who shanghaied more people than any other person in San Francisco,” Passetti said. “He actually kept ledgers and notes that they found… Historians are aware of like 20,000 people.”

With the bar as his hunting ground, Laflin would drug men and sell them to work on ships. These men would wake up to the sound of waves crashing against the outside of the ship, having no idea where they were or where they were going.

The Old Ship saloon was home to many known shanghaiers, such as Diedrich (Dick) Ahlers from 1883 to1889 and Warren P. Hermann from 1891 to 1896, according to their old records.

“It’s sort of a perfect recipe for a lawless zone,” Costantini said. “That’s why people could do pretty much what they wanted, and there was nobody there to stop them.”

Along with being a hangout for dangerous characters, the Old Ship Saloon was also used as a boarding house, hotel, bordello and safe haven for victims of the 1859 fire.

In its 171 years, the Old Ship Saloon has not ceased operations for more than six months, even during prohibition.

“When prohibition happened, the ownership changed,” Passetti said. “The ownership had already changed several times prior, but that was the first time they changed the name.”

To keep the business up and running during prohibition the Old Ship Saloon was converted into the Toscano Hotel from 1924 to 1936.

The original sign from when the Old Ship Saloon was re-named Babe’s Monte Carlo hangs inside the bar. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

Gus Piagnieri bought the Old Ship Saloon in 1937. Along with changing the name to the Monte Carlo Café, he also switched up the vibe of the bar to match what was trendy at the time.

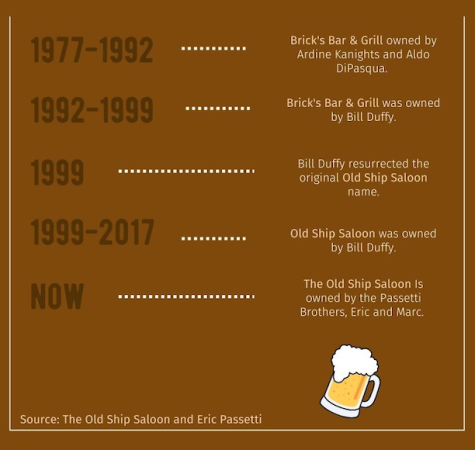

Throughout the following decades, the bar switched owners and names three more times before it was restored to its roots, when William Duffy changed the name back to the Old Ship Saloon. Duffy purchased the bar in 1974, and originally ran it under the name Bricks Bar and Grill, up until he decided to change it back to the Old Ship Saloon in 1999.

When the current owner, Eric Passetti, bought the bar with his brother Marc Passetti in 2017, they vowed to keep the name and rich history of the Old Ship Saloon alive.

The Beer Pairing

These pairings were made by John “Magic” Montes De Oca, Co-head brewer and Operations Manager at Barebottle Brewing Co.

Hazy IPA

Barebottle recommendation: Wonder Dust

ABV: 6.9%

Gold miners and risque voyagers weren’t the only ones to arrive in the San Francisco port by boat in the 1800s. India Pale Ales (IPAs) were brought over from Great Britain to ports all over the United States.

“The reason that beer style really took off was because people started marketing it as prepared for the Indian market,” Jeff Alworth, the author of The Beer Bible, said. “It gave it that kind of quality of exoticism.”

These early British style IPAs were incredibly strong and bitter due to the large amount of hops used.

Hops are the flowers from the hop plant. When added in the brewing process, hops give the beer a naturally bitter and piney taste. These beers originally would have smelled and tasted like a fresh forest of pine needles, mixed with an ounce of dank marijuana. Hops also worked as an antimicrobial that would keep beer fresh during its long journey across the seas.

When IPAs started being brewed in the United States, they were still too hoppy and bitter for many American beer drinkers of the time. Even when the original Northeast Hazy IPA, Heady Topper, was introduced in 2004 by The Alchemist Brewery in Waterbury, Vermont, it was still incredibly bitter.

Once brewers unlocked the potential of American hops and took advantage of the rich resources and wet weather in the Pacific Northwest, the juicy, aromatic, flavorful modern day hazy’s were born.

“If you grow American varieties anywhere else in the world, in Europe, especially, it’s just not as expressive,” Alworth explained. “If you grow one of those European hops in America, at least on the West Coast, you get a really expressive version of it.”

The Pacific Northwest is home to many popular hops used in modern-day Hazy IPAs. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s 2021 National Hop Report, Washington produced 73% of the hops in the country.

Citra, Mosaic and Simcoe were some of the most produced hops in Washington in 2021. The expressive flavors of these hops range from fruity, floral and tropical to spicy and earthy.

“It would never have occurred to anybody for 1,000 years that you would not put the hops in the boil, particularly if you’re making a hoppy beer,” Alworth explained. “The way that Americans are making hops now is revolutionary, and nobody had ever used hops that way before.”

A GIF of Wonder Dust, a Hazy IPA, chosen by Montes de Oca, to compliment the Old Ship Saloon. (Source: Caroline Raffetto)

Just as the modern day Old Ship Saloon was built up from the old infrastructure below it, modern day IPAs were built up from the infrastructure of hops in the Old English version of the beer.

“With all the changes it’s become something almost unrecognizable, but it’s still at the heart the same thing,” John Montes de Oca, Co-head brewer and Operations Manager at Barebottle Brewing Co., said.

The modern IPA is the complete opposite of the old English-style IPA, just as the rough and tough Gold Rush era Barbary coast is now an up-and-coming, modern neighborhood in San Francisco.

“It has all this fruitiness and residual sweetness in a way that the old beers would have been very dry and bitter,” Alworth said. “They went through this whole transition, and it was mainly a function of brewers learning how to work with American hops, which were really potent and really expressive.”

Some of these modern-day double Hazy IPAs trick people into forgetting about their high ABVs with their juicy flavors and easy drinkability– some could call them the modern shanghaiers of the beer styles.

“You can give someone a hazy Double IPA that is just fruity, juicy, tropical and you’ll never know that it’s 8%, ” Montes de Oca explained. “Then it will knock them on their ass. It’s just like being shanghaied. You don’t know what’s happening to you at this bar, and then all of a sudden, you’re getting so drunk.”